October 15, 2021

Written By: Ross Sherman, Public Relations Specialist

Research By: Caroline Joseph, Research Analyst

If you read the news, you probably have seen the word “filibuster” a bunch recently. And it’s not just your imagination: use of the delay tactic has increased exponentially in recent years. The most recent example was when Senate Republicans threatened to filibuster a vote to lift the debt ceiling.

A filibuster refers to any tactic a lawmaker uses to delay or block a vote on a particular piece of legislation. Right now, all a U.S. senator has to do to filibuster is threaten something called a cloture vote, which they can do by email or text message. When the cloture vote is called, 60 senators have to vote to break the filibuster and move a piece of legislation to a final vote. And in a Senate with 50 Republicans and 50 Democrats, and in an era of extreme polarization, getting to 60 votes on anything is proving harder and harder.

Yes, the filibuster is an arcane Senate procedure – and it’s hard to explain it to someone without their eyes glazing over. But because it’s currently holding up a bunch of bills that have wide support among the public, including the Freedom to Vote Act, it actually has a huge impact on all of our lives.

The gridlock we’re seeing at the federal level got us thinking: Is the U.S. Senate’s filibuster rule normal? Are filibuster rules in the states resulting in the same level of gridlock and partisanship?

So we did some digging, and found that the U.S. Senate is indeed an outlier. Overall, it takes more effort in all 50 states to delay legislation than it does in the U.S. Senate. Going a little deeper, of the seven states that appear to have rules most similar to the U.S. Senate’s, none experience the level of dysfunction that the U.S. Senate does.

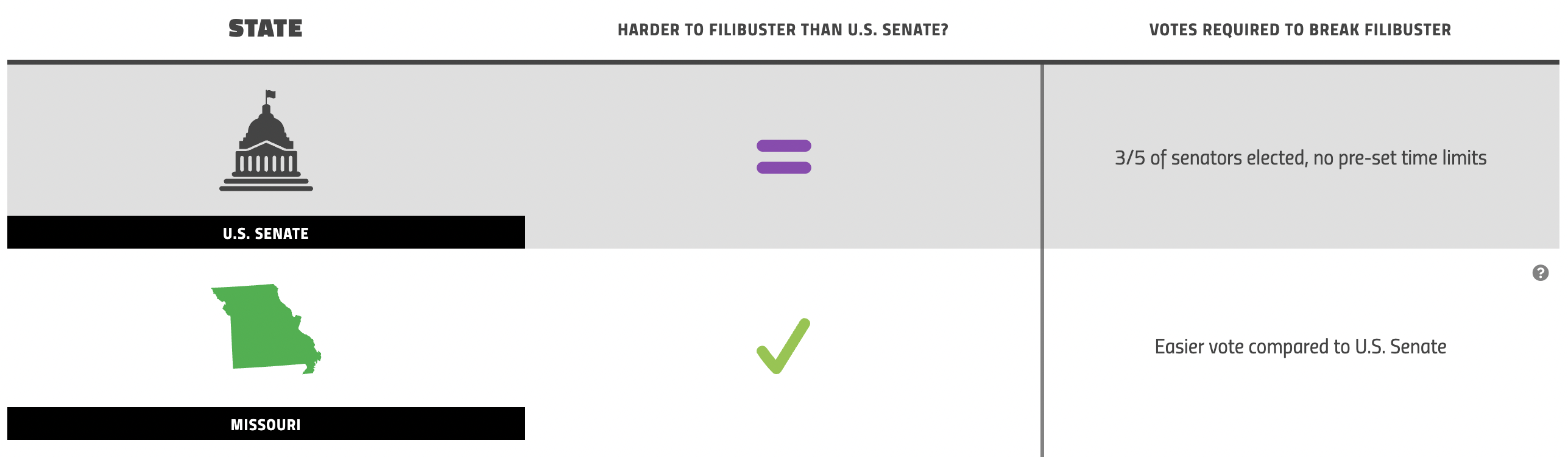

But rules alone don’t necessarily determine the ease or frequency of filibusters. Missouri, for example, doesn’t appear on paper to be a state that would have a filibuster problem. It only requires a majority of elected senators to end a filibuster, which is lower than the ⅗ elected senators threshold of the U.S. Senate. Also unlike the U.S. Senate, Missouri requires senators to physically be on the floor in order to maintain a filibuster.

In practice, however, the filibuster is used frequently by both parties in Missouri. The tactic is so commonplace that filibusters have been used for random personal grudges between legislators, and in one case, as a birthday present for a journalist’s wife. Phill Brooks, who has been a Missouri statehouse reporter since 1970, recalled a time when his wife was in the Capitol so they could go out to dinner afterward. Upon hearing that it was his wife’s birthday, senators promised a “present” – which turned out to be a “frivolous” filibuster. The Missouri Senate may also be one of the only chambers in the nation to have a bipartisan filibuster.

But even though the filibuster is used frequently in Missouri, it doesn’t mean that it’s similar to the U.S. Senate. Remember, Missouri only requires a simple majority of state senators present to overcome a filibuster, which is significantly easier to reach than the 60 votes required in the U.S. Senate.

Missouri’s state senators on both sides are also quick to point out this difference in how they use filibusters. State Sen. Caleb Rowden (R) recently said, “I like the process exactly the way it is. I think all the hoopla that happens in D.C. about Senate filibusters, it's so overtly political, it's almost stupid.” State Sen. John Rizzo, (D) agreed, adding, “It is part of the process, if you use it properly and correctly, which they clearly don't do in Washington, D.C.”

The bottom line is that Senate rules – and all government rules – should foster productive debate and action. In a democracy, voters elect representatives to enact their will through legislation. The current U.S. Senate filibuster has ground that process to a complete halt. The Senate need not throw away its identity as the more deliberative body of Congress entirely, but it must adapt to necessity, and it should look to literally any other state for ideas.

Democracy can't withstand this gridlock.