The cost of life-saving drugs has gotten out of hand. Big pharmaceutical companies pad the bottom line, while millions of Americans struggle to pay the bills. Public outcry has been fierce and widespread, but prices continue to skyrocket. Why?

These three outrageous Big Pharma scandals might shed a light on things:

$600 to save your life: Mylan’s EpiPen empire

When you’re in the middle of a life-threatening allergic reaction, you want the medicine you frantically scramble for to be a product you can trust. For many people, EpiPen was that product – but an explosive scandal tarnished its reputation.

Despite the fact that Mylan was paying only $1 to manufacture an EpiPen two-pack, the company jacked up the price for consumers from $100 to over $600 in 2016.

Mylan purchased the rights to EpiPens in 2009 when the market price was $104 for a two-pack. Over the next five years, Mylan spent nearly $8 million lobbying to make EpiPens mandatory in schools – and they were extremely successful. By 2016, 11 states required EpiPens and another 38 permitted their usage.

The state lobbying strategy in those years was simple, but ingenious: get people to recognize the brand and have them use the product for free.

“It’s kind of like the first hit’s for free. You want to start people off with your product, and getting these products in at schools is a great way.” – Nicholson Price, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan Law School.

And as the state lobbying strategy started working, the price of EpiPens kept creeping up, reaching $265 in 2013. And that was just the beginning.

In the same year, Mylan spent $4 million lobbying for the federal “EpiPen Law,” which gave financial incentives to states requiring Epipens. This meant that the federal government would subsidize the growing cost of EpiPens for cash-strapped states. It meant Mylan had hit pay dirt.

Once the federal government was on the hook, Mylan really began to take advantage. Over the next two years, the price doubled to $600. Outrage from parents and presidential candidates led to the company adding a savings card that would cover up to $300, but many were still being charged over $600.

And where was the competition to bring down prices? Nowhere. EpiPen dominated the epinephrine auto-injector market much like Kleenex dominates the tissue industry. And EpiPen’s monopoly was only possible because of forceful state and federal lobbying.

Opioid Epidemic: Crisis or Opportunity?

91 Americans die every day from opioid overdoses and politicians are scrambling for solutions. Unfortunately, some drug companies see this crisis as an opportunity to peddle expensive treatments and fleece patients.

Alkermes spent a staggering $19 million to ensure that their product Vivitrol got preferential treatment over their competitors. Their state-based lobbying campaign reaped big rewards, as 15 states created bills that referred to the drug’s unique characteristics, often by name.

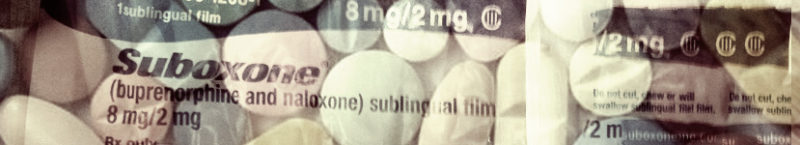

There are three primary treatments for opioid addiction: Vivitrol, methadone, and buprenorphine (Suboxone is the brand name formulation for buprenorphine). Vivitrol works like this: users get a monthly injection that blocks opioid receptors in the brain. By blocking the receptors, it becomes nearly impossible to experience a high from opioid use.

Meanwhile, methadone and Suboxone subdue cravings for opiates. Some compare this form of treatment to insulin for a diabetic.

Vivitrol’s year-long program is the most expensive of the three treatments. It can run up to $1,000 per month. For comparison, a year’s worth of buprenorphine is about half of that, and methadone only a quarter.

Alkermes marketed their product as a form of drug abstinence in opposition to their competitors, which they describe as another form of drug dependency. But there is no proof Vivitrol is more effective. In fact, many doctors still prefer Suboxone and its generic form, buprenorphine.

So how do you convince people to use your more-expensive and potentially less effective drug? Make it harder to use something cheaper. Alkermes lobbied to create red tape for doctors prescribing competitors’ medicines to patients. In Indiana, a state bill passed that allowed Medicaid insurers to use a process called prior authorization for buprenorphine. Prior authorization allows insurers to increase the paperwork necessary to prescribe a drug, adding a huge roadblock for patients who are going through opioid withdrawal.

“That really upset me. That is pretty explicitly saying that we’re going to hamper one medication more so than the other.” – Basia Andraka-Christou, researcher at the Fairbanks School of Public Health in Indianapolis

In Ohio, lawmakers passed a bill that directly interfered with how doctors prescribe medicine to patients. Under the new law, if a doctor wanted to prescribe Suboxone to more than 30 patients, they had to apply for a special license. This license also came with substantially more regulations. Here’s the thing: buprenorphine was already under significant regulation. Doctors needed a waiver to prescribe any form of buprenorphine in the first place. Even with the waiver, doctors could only prescribe it to 100 patients. The only reason for the added regulation was to increase Vivitrol’s market share.

“Their interest was in, is there anything they can do because Suboxone had such a toehold here in the state of Ohio, and they’re looking to expand their business.” – John Eklund, Ohio State Senator and author of the bill

Alkermes’ rivals were not above playing the game either. Reckitt Benckiser, the company which owns Suboxone, deployed their own strategy of “product hopping” in which they would make small changes, just big enough to get a new patent, a tactic they were later sued for using.

Martin Shkreli’s claim to fame: Daraprim

You may or may not remember the infamous “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli. Public outrage ignited in 2015 when the cost of Daraprim went from $13.50 to a jaw-dropping $750 per tablet, a 5000% increase. Daraprim is used to treat toxoplasmosis, which is a parasitic infection that mainly affects those with HIV, malaria, and cancer. After the price hike, the average cost of treatment rose from $1,130 to $63,000.

Experts denounced the move, as The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV Medicine Association said, “this cost is unjustifiable for the medically vulnerable patient population in need of this medication.”

After the backlash, Shkreli hired lobbyists to “buttress its interests on Capitol Hill.” Over 18 months later, the price had settled to a "mere" $375 per tablet, which was still an eye-popping 2500% increase.

If you’re wondering why pharma bros don’t get in more trouble, remember this: Big pharma companies spend approximately $240 million lobbying Congress every year – about double the $120 million that the oil and gas industry spends.